My first completed book of the year was The Blazing World: A New History of Revolutionary England, 1603-1689 by Jonathan Healey. I found it a well-balanced presentation of the kind of historical period I find really fascinating. It is unapologetically narrative history, but I didn’t find it too detailed. Through anecdotes and what data is available, it manages to emphasise (if not quite centre) the experiences of regular men and women in a way that stops it from being entirely a “great men of history” book.

The 1600s were a frantically busy century which (among many things) saw England abolish the monarchy and become a republic before eventually settling on a recognisably modern constitutional arrangement. And while this book conveys this sense of jolting change, I was also struck by its reflections on a couple of precious moments that offered paths not taken. In particular, the Putney Debates were a brief period of just a few weeks where it looked like Leveller politics might actually produce a democratic republic in England, with a broad franchise and freedom of religion. This more than a century before the American and French revolutions. You can’t help but be romantic about how things might have turned out differently (and this book definitely indulges you), but alas.

A lot of what I wanted to get out of this book was an ability to assess Cromwell. Knowing little about him, it’s easy to see him as either a brutal protestant bigot and military dictator, or proto-democrat who tried and failed to abolish the monarchy. As you’d expect the impression that’s left here is more nuanced. Firstly, Healey mostly absolves Cromwell of the Puritan extremes of his regime, such as death penalties for adultery and the ban on Christmas (yep!). These Puritan ideas predated Cromwell and they were mostly enacted by Parliament. We also learn about Cromwell’s quiet loosening of the exclusion of Jews from England. 360 years after the Edict of Expulsion, he invited the chief rabbi of Amsterdam to England, gave him a state salary and supported the establishment of a synagogue in London.

Overall though, the image of Cromwell is of a brilliant and lucky soldier whose religiosity made him a bit of a bit of a weird dude, not really capable of delivering on the republican potential of the 1640s. Other clearly more impressive constitutional thinkers like John Lambert might well have ended up as Lord Protector. Instead, we get things like the spectacle of Cromwell humming and hawing about reclaiming the title of King. He eventually declined to re-establish the monarchy not under any constitutional principle, but because he interpreted the victory of Parliament in the Civil War as God’s rejection of the monarchy. Even his superficially radical re-admission of Jews into England was motivated by a desire to convert them and hasten the Second Coming of Christ.

There’s a long reflection on the rise of Natual Philosophy (ie science) and its significance. But the huge ramifications of England’s 17th century outside of England are not a focus. The horrors of Cromwell’s reign in Ireland is mentioned but not explored. And in (mostly) ending its political history with the Glorious Revolution, the book enables an England-centred view of it having been a “bloodless revolution” and elides its catastrophic echoes in Ireland and Scotland.

Most significantly, the 1600s saw the start in earnest of Britain’s horrific role in India. We learn about Charles II’s Portuguese wife Catherine, how she was humiliated by his infidelity and slandered during the Popish plot scandal. But we didn’t learn that her dowry included a handful of formerly Portuguese islands in modern-day Bombay. By the end of the century these would form the foothold from which the East India company would pillage the world’s wealthiest civilisation. As fascinating as the English history of this century is, in terms of sheer economic and human impact its largest effect was probably outside its borders.

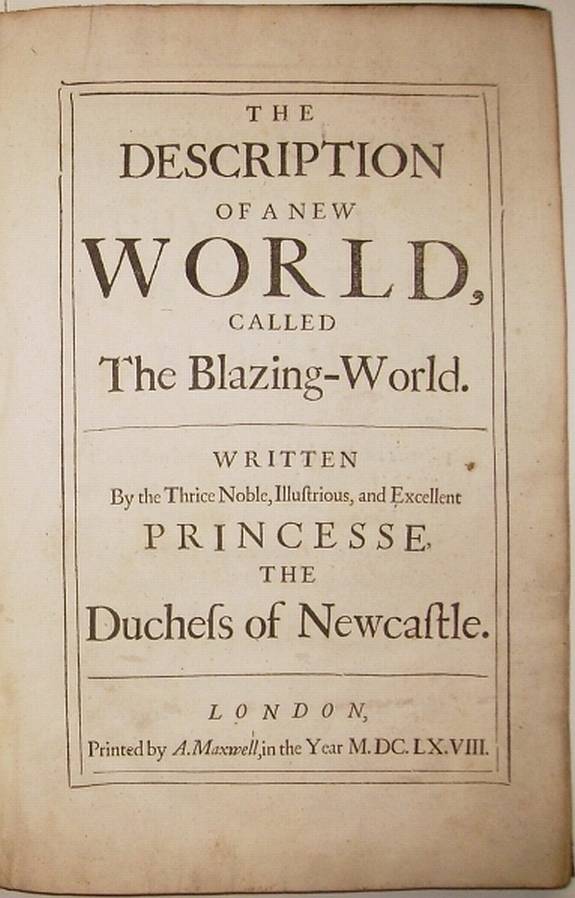

The title of Healey’s book comes from The Blazing World by Margaret Cavendish, Which I read immediately after the history of revolutionary England. The Blazing World is almost certainly the first work of English-language science fiction written by a woman.

Healey characterises The Blazing World as an attempt to process the extraordinary change seen by those who lived in Restoration England. In it, the unnamed protagonist journeys to The Blazing World, a land of half-human half-animal creatures. She is made their Empress and debates their leading minds, articulating a thinly veiled criticism of the scientific ideas beginning to spread in 1660s England. The newly popular microscope might have produced Hooke’s Micrographia, but it didn’t stop fleas from biting. Eventually the Empress communicates with the soul of Margaret Cavendish, becoming her closest friend. Together they come to the aid of the King of England, using the scientific powers of The Blazing World to subjugate all of Europe to the English throne. What a way to process the trauma of the abolition of monarchy!

But, as Healey only briefly considers, the facts of Cavendish’s life are a glimpse of the most glaringly absent reform or revolution in 17th century England. Cavendish never attended school. When she became the first woman to attend the meeting of the Royal Society, its fellow and later president Samuel Pepys wrote her off as a “mad, conceited, ridiculous woman”. In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf cries out at how the patriarchy lead to the senseless waste of such a mind:

Margaret too might have been a poet; in our day all that activity would have turned a wheel of some sort. As it was, what could bind, tame or civilize for human use that wild, generous, untutored intelligence? It poured itself out, higgledy-piggledy, in torrents of rhyme and prose, poetry and philosophy which stand congealed in quartos and folios that nobody ever reads. She should have had a microscope put in her hand. She should have been taught to look at the stars and reason scientifically. Her wits were turned with solitude and freedom. No one checked her. No one taught her…

What a waste that the woman who wrote ‘the best bred women are those whose minds are civilest’ should have frittered her time away scribbling nonsense and plunging ever deeper into obscurity and folly till the people crowded round her coach when she issued out. Evidently the crazy Duchess became a bogey to frighten clever girls with.

This is a society that was beginning to dabble in truly radical notions like “one man one vote”. It’s just horribly, brutally sad to think of how much human potential was wasted in a century where essentially none of these “great men” contemplating extending their program of political reform to half the population.